Theater For The New City

Dream up Festival

7 September 2025

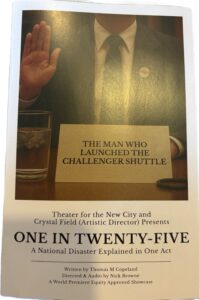

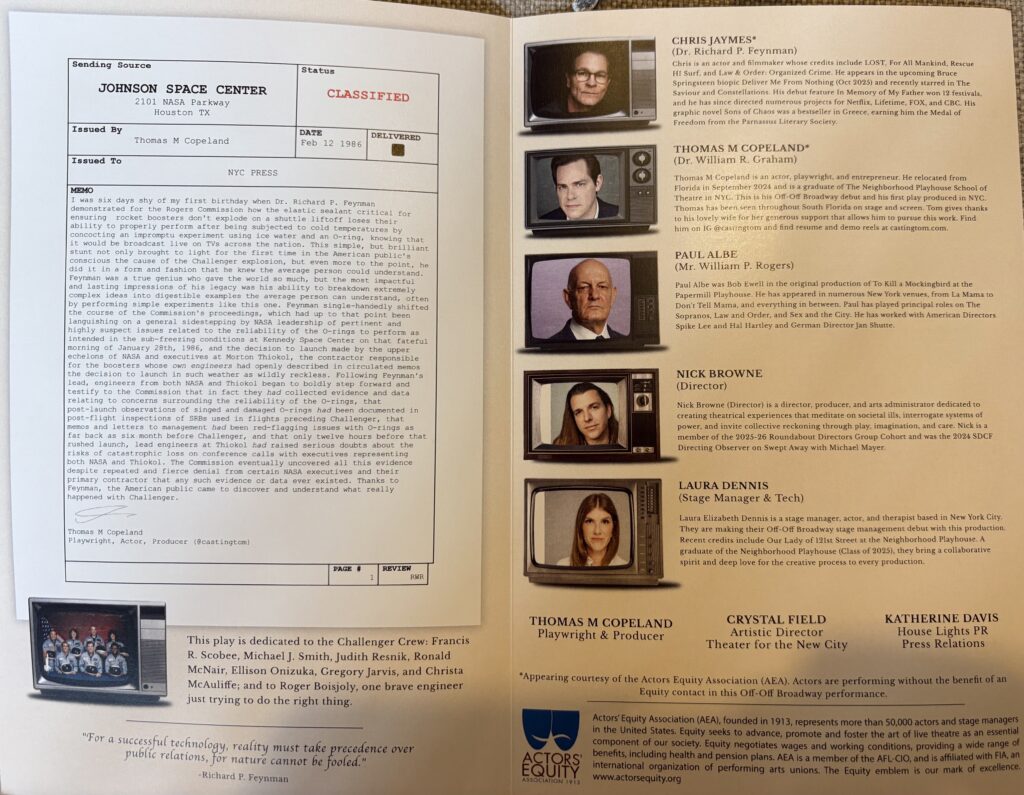

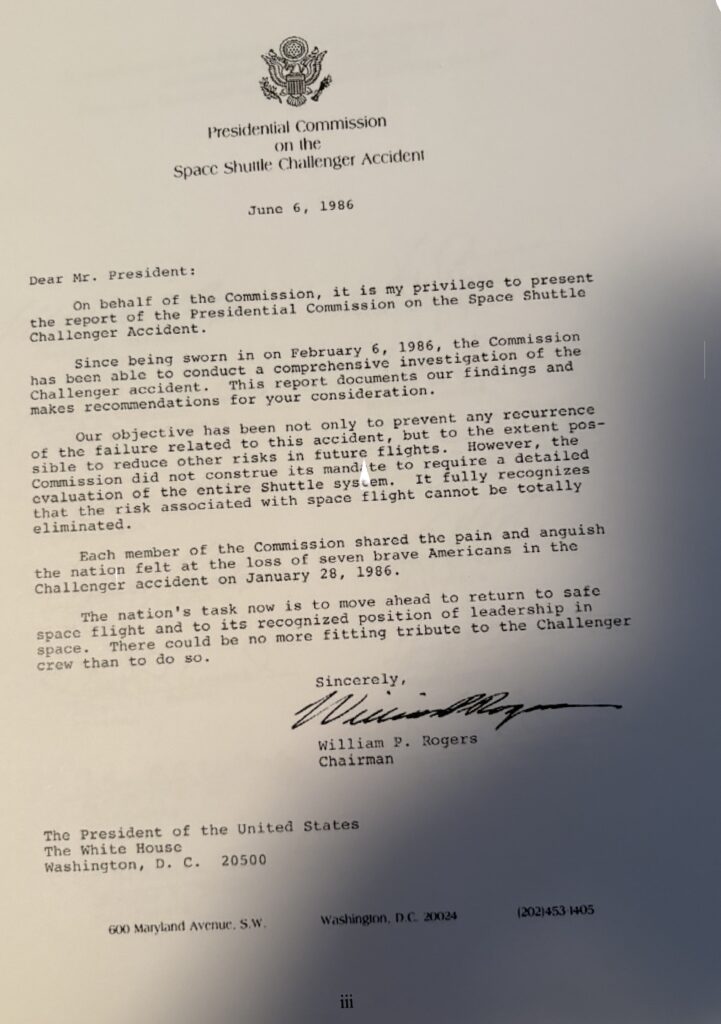

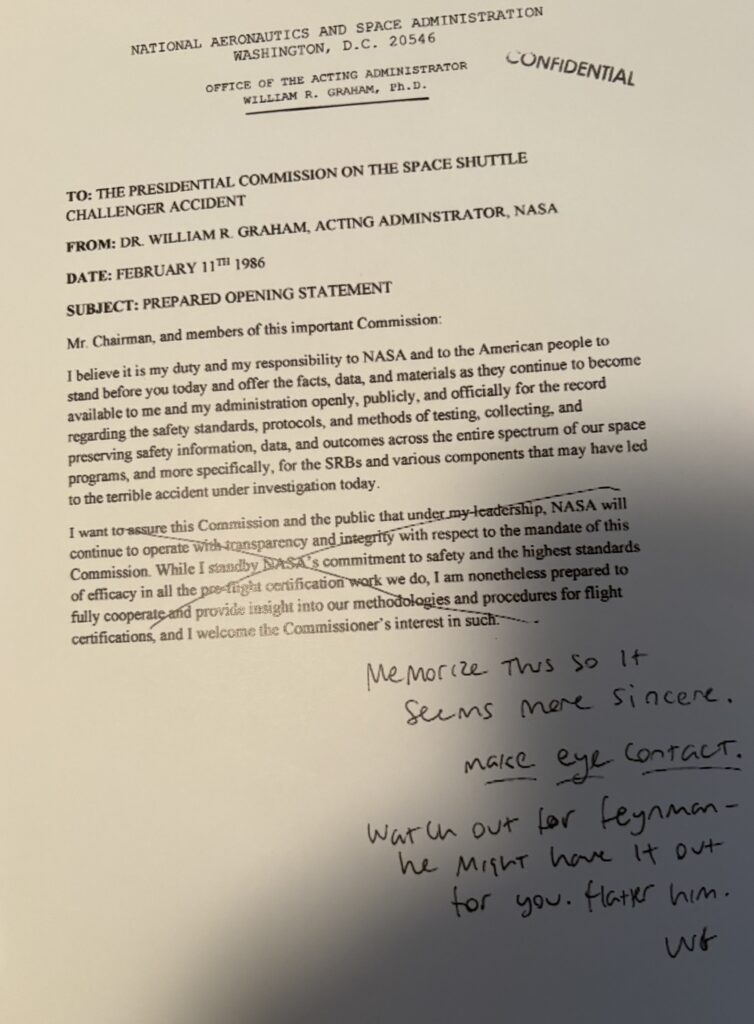

This show centres around The Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident, also known as The Rogers Commission. The entire show takes place within the walls of one room and the audience becomes more than just spectators — we become the members of the gallery/members of the commission that is being appealed to as Dr. William R. Graham, the acting administration for NASA (played by Thomas M. Copeland) tries to convince Dr. Richard P. Feynman, a commission member (played by Chris Jaymes) that there was no way to see this accident coming. The head of this commission is Mr. William P. Rogers (played by Paul Albe).

I think the easiest way to explain this commission, in its simplest form, is to compare it to a criminal trial. Dr. Graham would be the defendant, Dr. Feynman the prosecutor, Mr. Rogers the judge, and the audience would be the members of the gallery.

The show opens with audio clips taking the audience through the entirety of the day that the shuttle exploded. The shuttle launches, the excitement in people’s voices, the news casters announcing the launch, then the panic, the screams of terror, the horror, the news stations reporting that the shuttle exploded, and finally President Ronald Reagan addressing the American public to assure everyone that we will find out what went wrong so that it never happens again.

And it is here that we meet the characters in the show. Dr. Graham is a physicist who is the current acting administrator of NASA. That means that he and his team are the people who do the mathematical equations needed to figure out the risk of catastrophic failure for the space launches. It is worth noting that while Dr. Graham is not the person who is directly doing these math equations, he is the person who signs off on the work and is ultimately responsible in making sure that all factors have been taken into account when putting together these equations and that the math is correct.

Mr. Rogers is the appointed chairman of the Rogers Commission. He was appointed by President Reagan and was a former Secretary of the State and a former Attorney General. He is the man that must give the results of this commission to the President (and therefore may face any wrath that Reagan may have if the results do not shine a positive light on NASA).

Dr. Feynman is a theoretical physicist and was assigned to be a member of the Rogers Commission. He is the voice of reason in this show (and historically) as he is the only one who can see beyond the mathematical equations that are supposed to guarantee safety and understand that lives aren’t promised by an equation because there are always outside factors that an equation cannot account for.

The staging of this show is simple, yet effective. The vast majority of the show consists of the three actors sitting behind desks. However, that is the only type of staging that would realistically make any sort of sense for the setting. There were two beautiful moments that broke from this: the first is when Dr. Feynman shows everyone at the Rogers Commission the risk factor report that breaks down what was used to determine if any components of the solid rocket boosters needed to be replaced (this is vital because a faulty O‐ring was found to be the cause of the explosion and with there being a massive oversight in how risk factors were calculated — mainly the effects of how cold weather changes the ability of the O‐ring to function properly — the whole disaster could have been avoided). The second time comes when Dr. Feynman performs a simple, elementary school level, science experiment to prove his point as the commission progresses. Dr. Feynman (as well as all of the characters on stage) has a glass of water in front of him, with a clear water pitcher next to it, full of ice water. So it makes for a stunning visual for Dr. Feynman to pull an actual O‐ring out of his pocket and show everyone how easily it can be bent and contorted into different shapes. He then fills his glass with water (critically, there was no ice in the pitcher in front of him), walks across the stage to Dr. Graham and very awkwardly, but also with conviction reaches his hand into Dr. Graham’s pitcher of ice water and grabs a handful of ice, which he places into his cup of water. Dr. Feynman then places the O‐ring into the cup of ice water for maybe 30 seconds before being able to show everyone at the commission how the O‐ring, in such a short period of time, became brittle, unable to change shape and now only able to snap if it were forced to try to expand. It was an unseasonably cold day in Florida the morning of the Challenger launch. The effects of cold temperature on the O‐rings was something that should have been and could have easily been tested. But it wasn’t.

Which brings us the point of this show — human error is inevitable. Even if humans create machines to do everything for us, it still is only as good as the person who programmed it. It also takes other humans to catch the errors of others. A machine simply cannot reliably take in all potential contributing factors that is needed for operations that can be life or death. So while it is impossible to remove human error altogether, it’s also impossible to exist without humans playing a part in everything. So who should take the blame when things go wrong? Whether it’s humans wrongly assuming they’ve covered all of their bases when putting together a program or a risk factor assessment or simply not checking the work of those below you and still allowing that work to make it through and into the hands of the bosses — it’s the fault of someone and people should be held accountable.

One thing that struck me throughout this show was just how little of a factor it was that there was a teacher on board of that shuttle. In fact, it is only briefly mentioned at all and that’s in one line spoken by Dr. Feynman in which he is admonishing the choice of President Reagan and NASA to even send a teacher to space because it was really done as a publicity stunt to improve relations with the general American public. And that’s horrible — but it isn’t the main point of this show. In the grand scheme of things, her being a teacher and not an astronaut is inconsequential because there were so many times that a human could have stepped in and stopped the launch if only someone had done more than just assume that what was already being done was correct.

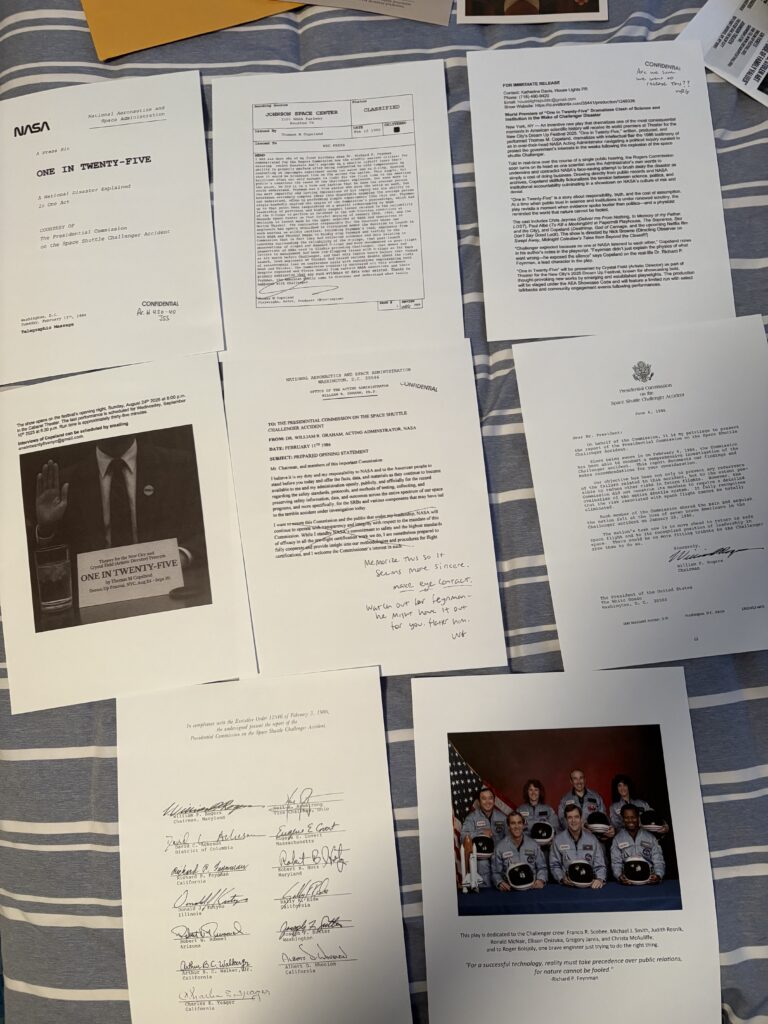

The icing on the cake for this show is the press kit. The detail put into making “confidential files” from NASA showing the thought processes and ideas of the different characters (and from the characters’ own perspectives) was simply beautiful.

All in all, this show is deeply thought provoking. I did not expect to be enthralled by this story because honestly, it occurred three years before I was born. I know about it, I learned about it in school, I have even seen the video footage. But I never truly understood how big of a tragedy this was before seeing One In Twenty‐Five. And it is not because of the loss of life — it is because the loss of life could have so easily been avoided.

I find it interesting that this show comes down to the number “4%”. When something goes wrong once out of every twenty‐five times it is tried — that is something going wrong 4% of the time. And 4% sounds like a really low percentage. But once it is laid out as being once out of every 25 attempts that there is catastrophic failure… suddenly 4% is huge.

Leave a Reply